Introduction

I find myself reaching for BinaryNinja more and more these days, navigating and experimenting with the API. This post will cover a few things I’ve picked up over the last few months by fiddling around.

Global variables

The integrated python interpreter comes with a few context-sensitive global variables which can be used in your snippets of code. You’ll find these here.

Patching

As you may know, BinaryNinja has extensive patching features built-in, accessible directly from the GUI - you can patch to NOP, edit one line, assemble an arbitrary amount of instructions or even compile from C.

But you can also write some code snippets to do some more complex patching tasks. It’s as simple as data = bv.read(address, length), process the data, then bv.write(address, data).

Hex editing

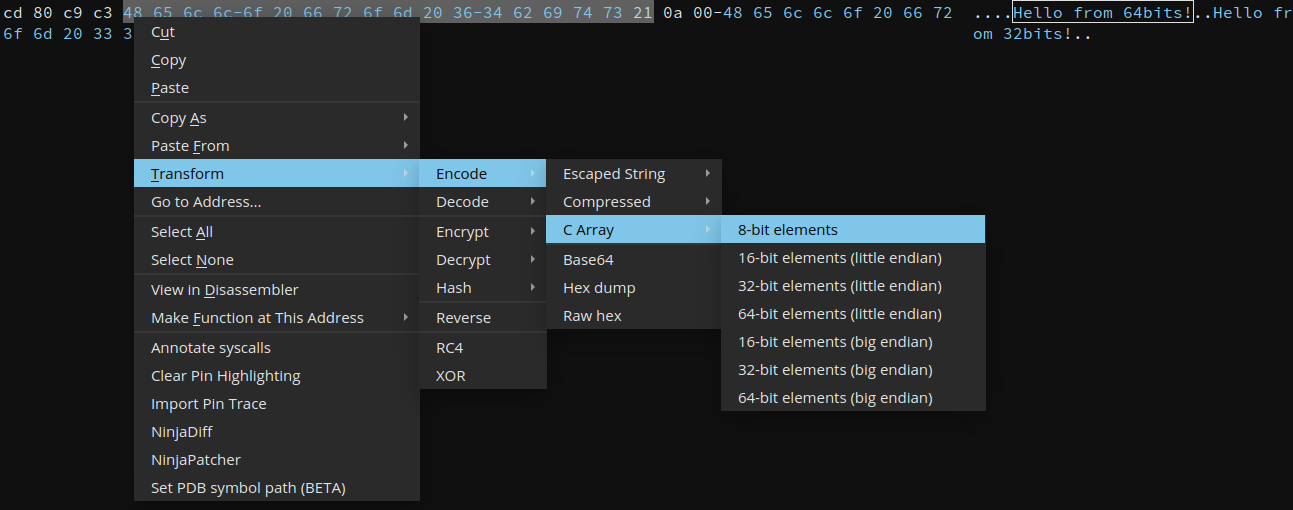

I find BinaryNinja to be a very good hex editor, especially given the built-in tranform tools for common tasks such as XOR-ing with a key, decoding base64 or grabbing the data to use elsewhere.

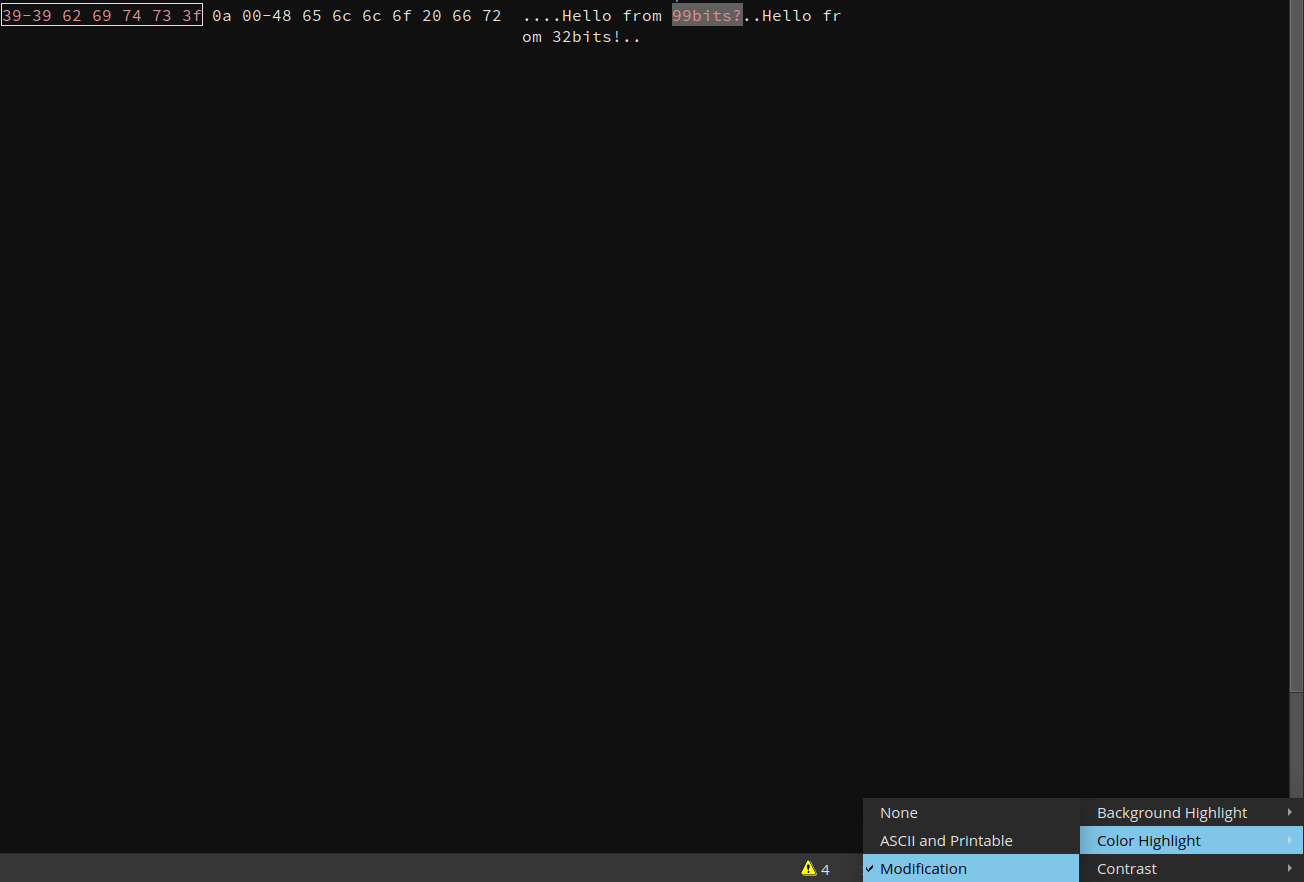

There are a few coloring options available: you can make ASCII values stand out or only colorize values which have been modified (through the GUI or the API). One use case for this feature would be to take two memory dumps of the same process at two different points in time and patch the bytes which have been changed. Coloring the bytes can help see patterns in the way the data was written.

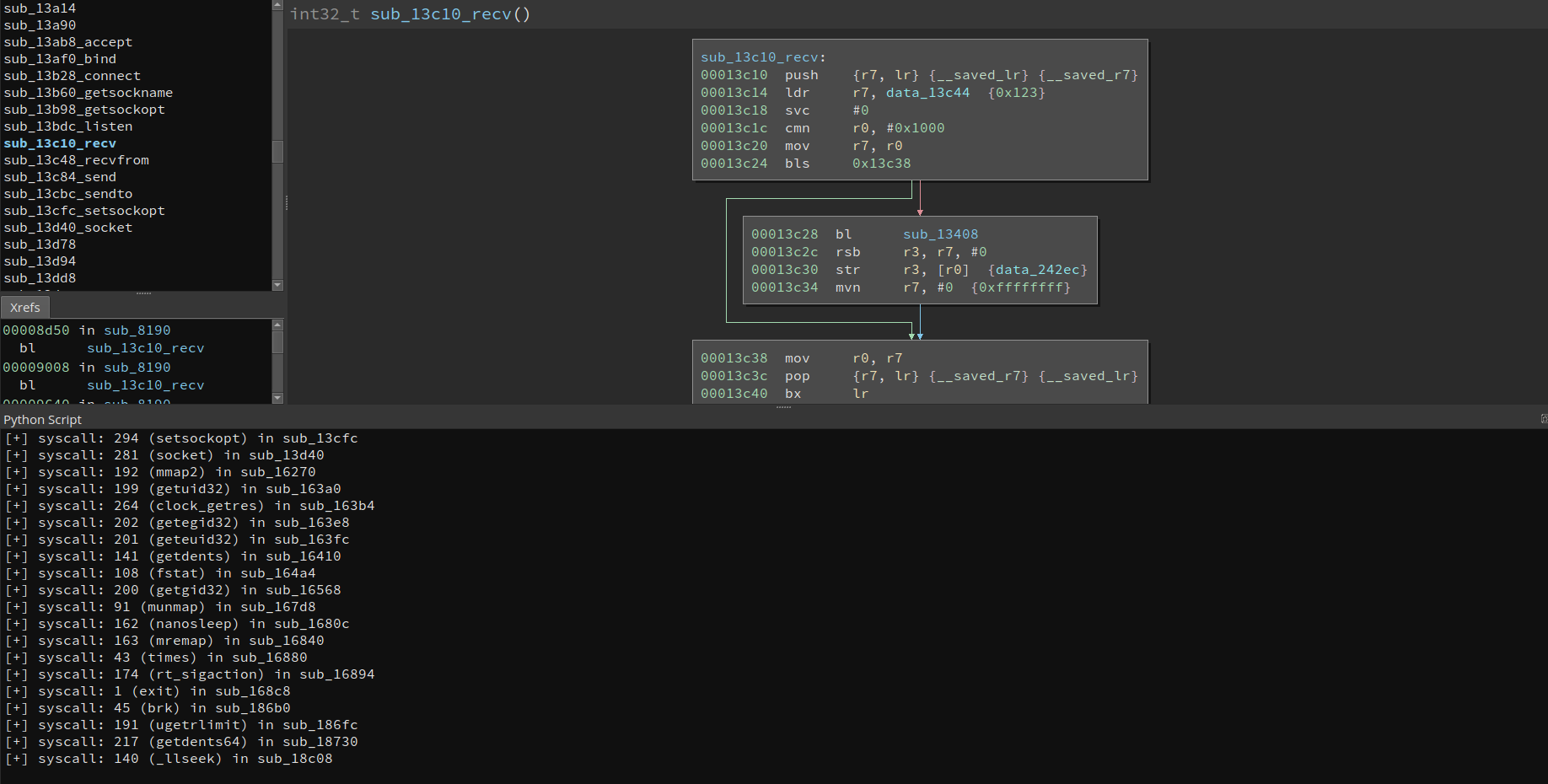

Syscall-based function renaming

This has been done before by great people in the community, such as carstein.

I have a small snippet (and a large JSON) which I use when analyzing statically linked ARM binaries, which uses the MLIL.

for func in bv.functions:

mlil_inst = list(func.mlil_instructions)

for mi in mlil_inst:

if mi.operation == MediumLevelILOperation.MLIL_SYSCALL:

try:

syscall_num = mi.params[0].value.value

print "[+] syscall: " + str(syscall_num) + " (" + str(arm_syscalls[syscall_num]) + ") in " + str(func.name)

func.name += '_' + str(arm_syscalls[syscall_num])

except:

pass(Note to self: I should probably refactor this at some point, replace the try-except block with something more sane, such as hasattr). This will also rename functions by appending the syscall names, which makes analysis much easier, since most library functions are wrappers over native syscalls.

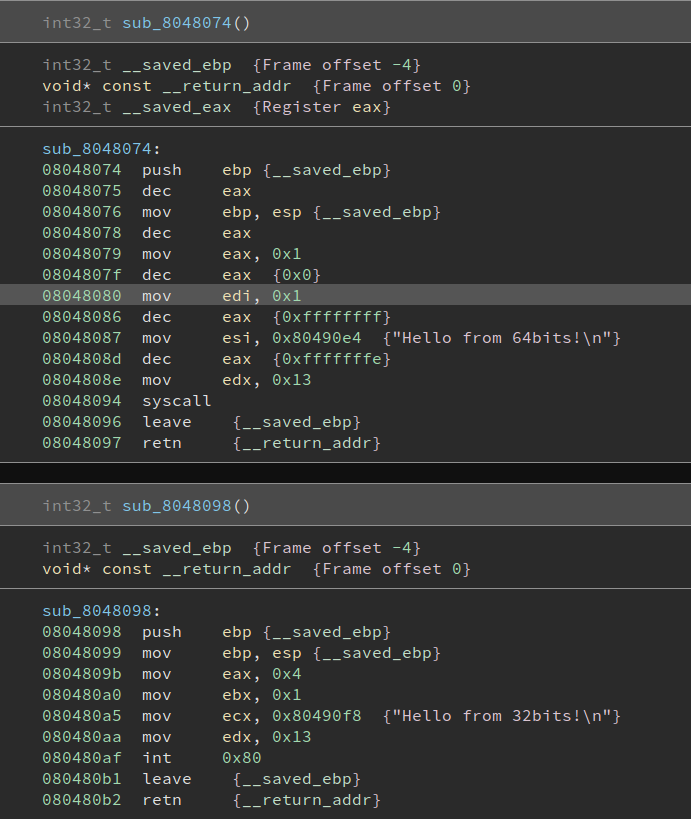

Mixed platforms

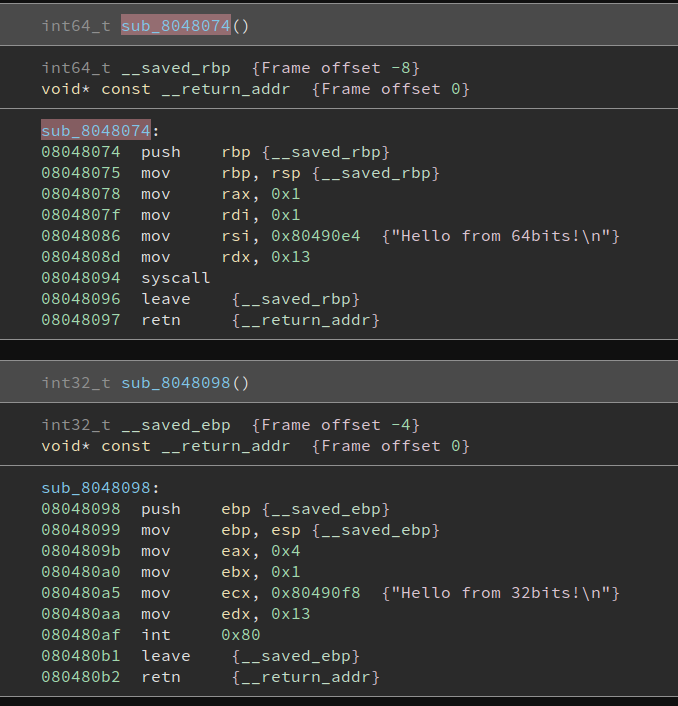

Recently, I had to deal with solving a CTF challenge which mixed 32bit and 64bit code. If you never came across such a challenge, you should know that most tools are lacking when it comes to dealing with them. Naturally, I assumed BN would also suffer from this shortcoming.

Let’s take a look at a short example (assemble with FASM; I couldn’t manage to coax NASM to create an ELF32 with 64bit code in it):

format ELF executable

segment readable executable

macro swap32_64 dst {

use32

push 0x33

push dst

retf

}

macro swap64_32 dst {

use32

push dst

mov [esp+4], dword 0x23

retf

}

use64

hello64:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, hello64_str

mov rdx, 19

syscall

leave

ret

use32

hello32:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

mov eax, 4

mov ebx, 1

mov ecx, hello32_str

mov edx, 19

int 0x80

leave

ret

entry $

_start:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

call hello32

swap32_64 call64

call64:

call hello64

swap64_32 do_exit

do_exit:

mov eax, 1

mov ebx, 0

int 0x80

leave

ret

segment readable writable

hello64_str: db "Hello from 64bits!", 0xa, 0

hello32_str: db "Hello from 32bits!", 0xa, 0

As you can see, Ninja disassembles the function as 32bit code. It’s still readable, but that’s because this is a simple example, with very little instruction variety. We can actually undefine this function and use the API to create it as a Linux x86_64 function by explicitly specifying the Platform in the BinaryView.create_user_function method.

x64_func = bv.get_function_at(here)

bv.remove_function(x64_func)

bv.create_user_function(here, Platform['linux-x86_64'])

Much better!

This approach can also be used when dealing with obfuscation that uses Virtual CPUs. You need to define your own Architecture (there’s a great post on RET2systems on how to write your own custom architecture plugin) and then define functions, specifying the current Platform and new Architecture. In this way, you won’t have to switch tabs/notes/files; you can have consistent offsets, jump targets and so on in a single view.

Closing

That’s it for this post! If you found this post helpful, have any questions or comments, or would like to share some of your own tricks, drop me a line on Twitter.